Mysterious Medieval book stumps code breakers after 100 years of study

by Gael Stirler

(August, 2012)

|

|

What would you do if you heard that the most famous linguist in the world, the Jesuit scientist Athanasius Kircher(1602¿1680), was writing a book on codes and had requested other scholars send him examples from their libraries especially if you had a very old book in your possession that you wanted decoded? You would write him and that is what Georg Baresch of Prague did In 1639,

"...and since such a Sphinx in the form of writing in unknown characters was uselessly taking up space in my library, I thought I would not be unjustified in sending this enigma to be solved..."

So Baresch sent copies of several pages of the code and expected it would be broken in no time. Eighteen months later he was still waiting so he sent another letter with a messenger this time. But he was never to learn the meaning of this mysterious book for even to this day, after hundreds of the world's best cryptographers, linguists, physicists, botanists, and astrologers have tried, not a single word of this 234 page document has ever been successfully translated.

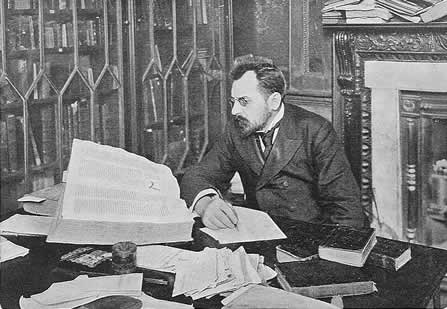

The mysterious book is now known as the Voynich Manuscript after the antiquarian Wilfrid Voynich who bought the book from a Jesuit monastery and published the first history of its origins. Voynich believed that the book had been sold to the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II of Hapsburg for 600 gold ducats (approximately $30,ooo in modern US dollars) based on a letter that accompanied the book when he bought it.

|

|

According to Voynich, Georg Baresch of Prague continued trying to break the code without help from Kircher until he died and bequeathed the book to his friend Johannes Marcus Marci. Marci sent the book to Kircher hoping to fulfill Baresch wish to have it decoded. When Kircher died 15 years later, his books and notes and the indecipherable manuscript were given to a Jesuit monastery. In 1870 the army of Vittorio Emanuele II captured Rome and confiscated the wealth of the Jesuits including their libraries. Many of precious books were hidden in the homes of wealthy sympathizers and labeled the property of private citizens so that they wouldn't be siezed. Thus the Voynich MS was given to Peter Beckx for safekeeping and moved to the Villa Mondragone. In 1892 the Jesuits bought Villa Mondragone and began badly needed restoration. Twenty years later they sold many old books, including a mysterious handwriten book in an unknown language, to antique book dealer, Wilfrid Voynich.

|

|

After Voynich's death, his widow Ethel gave it to her friend Anne Nill, an antique book specialist. She died only one year later while in the process of selling it to Hans P. Kraus. Kraus eventually donated the Voynich MS and the letters, notebooks, and papers associated with it to the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library of Yale University where it reside to this day as Beinecke MS 408.

Over the intervening 100 years this book, known as the Voynich MS (manuscript), has been the passion of thousands of scholars worldwide. It's been written about in numerous artic

les, books, and documentaries. To commemorate the 100th anniversary of this event, a celebration was organised in the same Villa on 11 May 2012. This event brought together experts and interested people from all around the world to present scholarly papers and explore new theories of its orign.

Voynich believed that the book was a hermetic (alchemical) text written in the 13th century by the monk Roger Bacon (1214?-1294). John Dee (1527-1608) a physician close to Rudolf II (1552-1612) had a large of collection of books on astrology and alchemy many written by Roger Bacon. Voynich believe it was Dee who convinced the Holy Roman Emperor to purchase the book because it was written by Bacon and would reveal the hidden mysteries of the cosmos. But other researchers point out that Dee's close advisor, Edward Kelley (1555–1597), was a self-professed prophet who "spoke to angels in an unknown tongue" and had been expelled from England for fraud and forgery. This has led many Voynich scholars to suspect that Dee or Kelly fabricated the book to cheat Rudolf II out of a large sum of money. This would indicate a late 16th century or early 17th century origin and that the text is pure nonsense.

Some scholars question whether Rudolf II ever even owned it. The only reference is in a letter written 50 years after his death. Could it have actually been written after his death?

Richard SantaColoma, a Voynich scholar and blogger, proposes that the book may have been fabricated in Prague between 1610-1625 by someone other than Dees or Kelly. His theory proposes that the cylindrical towers or jars in the illustrations are early microscopes and that many of the mysterious pictures in the book are micrographia (drawings of microscopic things) of diatoms, pollen, and cells.

|

|

Other theories delve into the personalities and rivalries surrounding the courts of Emperor Rudolf II and James I of England. One of the first scientists to write about microscopes was our old friend Kircher who worked with the microscope maker Cornelis Drebbel (1572–1633). Coincidentally Drebbel learned how to make microscopes at Rudolf's court from the inventor of the compound telescope himself, Johannes Kepler. Is it possible one or both of them wrote the Voynich MS or made the illustrations?

In this case the book may have been coded to hide their discoveries from rivals or enemies. If true, then decoding could shed light on the earliest research into the invisible realms. The writer of the Voynich MS, if he were seeing microscopic organisms that no one else had ever seen or reported may have imagined a tiny world filled with tiny people and set out to write about them. But it would have been so radical an idea that he had to protect his secret by writing in code lest he be accused of witchcraft, imprisoned, tortured and killed.

|

|

This was not a frivolous fear. In 1600 Johannes Kepler and his family were banished from Graz for refusing to convert to Catholicism and in 1615 his own mother was accused of witchcraft partly based on a "distorted, second-hand version of Kepler's Somnium, in which a woman mixes potions and enlists the aid of a demon." Somnium, has been called the first Western work of science fiction ever written since it was a story about interplanetary travel. Kepler wrote a long treatise explaining how the novel was an allegory to illustrate deep scientific truths like lunar geography.

For eleven years Kepler was the court astrologer and mathematician to Emperor Rudolf II. This brought him into close contact with Drebbel, Kircher, Dees, Kelly, and his great rival, Galileo. Then as now scientists were in competition to be the first to publish their discoveries. But sometimes the fear of criticism from the Church, which could destroy careers and families, may have caused bizarre clandestine behavior.

So here we have a group of scientists--

- who were making discoveries with telescopes and microscopes

- who were afraid of being accused of witchcraft based on their writings

- who were known to have written allegorical, science fiction novels

- who may have belonged to one or more secret societies like the Rosicrucians or the Knights Templar.

Is it so hard to imagine that one or more of them created this book to hide their discoveries until they were better understood or the world was better ready?

SantaColoma doesn't believe that the book is a notebook of observations made with a microscope but an elaborate homage to another novel written sometime between 1608 and 1623 by Sir Francis Bacon called Utopia, The New Atlantis. This novel was about a fictitious land filled with marvelous plants and animals, where the people grafted the plants in wondrous ways to create new plants and crossbred animals to make new species. The plants were forced to bloom and fruit out of their natural season and to produce sweeter fruit or more abundantly than they were wont. The inhabitants bathed in medicinal waters and even created artificial ponds for bathing. They also had optical instruments that allowed them to see very small objects.

The Voynich MS seems to illustrate many of these descriptive passages as though it were actually an artifact of this fictitious world. SantaColoma proposes this may be a faux book meant to look like it came from this Utopia. The charm of this theory is it casts the Voynich authors as the world's first science-fiction geeks who write fan fiction and make up written languages in their downtime as a kind of homage to their favorite author!

|

|

But the most mysterious development in the Voynich arena comes from the University of Arizona Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Laboratory in Tucson, Arizona. In December of 2009, a team of scientists headed by Greg Hodgins determined that the parchment had been radiocarbon dated to AD 1404 to 1439, or 100 years earlier than most theories. This totally disproves the monk Roger Bacon having anything to do with it and makes it less probable that it came from the scientists in Prague.

Could that lead us back to Voynich himself? Voynich never revealed exactly where he got the manuscript saying he may want to buy more objects from his source in the future. It was only revealed after his death that it was from Villa Mondagone. More likely Voynich wouldn't reveal his source because he hadn't obtained the proper export documents from the Italian government. But doesn't it also imply that it could have been a clever forgery? It seems that in 1908 Voynich bought a large antiquarian bookstore Libreria Franceschini in Via Ghibellina in Florence. This was a trove of half a million books and manuscripts mostly confiscated from churches and monasteries during the Risorgimento fifty years earlier. Along with the books were numerous sheets of very old, unused parchment and empty ledgers—any of which could have been used to forge a document that would pass even an expert eye as a medieval notebook. Perhaps he was the forger or he inadvertently bought a forgery that he thought was real. Or maybe it is the work of one of the world's greatest scientists. After 100 years of trying to decipher its meaning and history, the Voynich Manuscript still defies understanding.

References

- Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library of Yale University

- Voynich Optics a bog by H. Richard SantaColoma

- Wikipedia

- THE VOYNICH MANUSCRIPT SITE

- Video: Naked Science—The Book That Can't Be Read.

>

|

If you want to add this article to your list of favorites or email it to a friend, please use this permanent URL, https://stores.renstore.com/-strse-template/1208A/Page.bok. Permission is granted by the author to quote from this page or use it in handouts as long as you include a link back to Renstore.com. |

|

| Next Article |

|