It's a wonder that they made it to adolescence.

by Gael Stirler

(August 17, 2013)

Infancy

Children in the middle ages and Renaissance were divided by fate into two categories; nobility and common and their lives were very different depending on which group they belonged to. Right from birth, the children of the aristocracy and the aspiring wealthy classes were tended by servants, nursemaids and tutors. A Prince might have two nurses, four cradle rockers, one or more chambermaids, and a laundress. As a toddler he would also have grooms that followed him making sure he didn't fall and ruin his expensive clothing. His mother wouldn't nurse because nursing was known to reduce fertility and she was required to bear as many children as possible to maintain the dynasty.

|

|

The mother of a commoner baby was likely to nurse her own child and therefore have a much closer relationship. But large families meant more work for Mother so the other children had to help with the youngest and rock the cradle, change diapers, do laundry, etc. Nursing was a welcome respite from work for both mothers and babies.

Small babies of both classes were kept swaddled in linen strips with darker bands criss-crossed over their bodies. This served to keep the babies warm and protected from insects, but its main purpose was to insure that the babies tiny limbs didn't grow crooked. This also kept babies from flailing around and falling out of their cradles which seems to have been a problem. Magistrate records of accidents and crimes tell of babies being strangled by the cords that held their hanging cradles, or falling out of wooden cradles and dying. On the other hand it was considered proper to leave a baby alone in a cradle while mother shopped as long as the baby was swaddled! Babies were given necklaces of large coral beads for protection from evil. Imagine that, they took a strangulation hazard like a cord, combined it with some choking hazards like bright red beads, and just for good measure added a pendant made of a sharp stick of coral. What could possibly go wrong? That's not all. There were even nursery rhymes about leaving a slice of bread and a knife in the cradle to keep bad spirits away from the baby.

Let the superstitious wife

Near the child's head lay a knife

Point be up, and haft be down

(While she gossips in the town)

This 'mongst other mystic charms

Keeps the sleeping child from harms.

Toddlers were in more danger since they could easily topple into the fire or a tub of water at any moment. Therefore they were often "tied to their mother's apron strings" or put in wooden walkers. There are depictions of small children on leashes or harnesses as well. About this time babies were weaned and they began to eat soft food called pap. Pap was made from boiled grains and milk or bread soaked in almond milk. Sometimes nurses would chew food with their own mouths then feed it to the babies with their fingers. This is reported as common right up through Tudor and Elizabethan times.

Infancy was considered to last up to the age of seven though it was marked with milestones for weaning, walking, and talking. Before seven girls and boys were treated the same and both lived mostly under the care of women in the nursery. They played with animal pets and toys like dolls, balls, hoops, noise-makers, miniature dishes, and little music instruments. But boys were allowed to play with knives, bows and arrows, toy swords and hobby horses.

Pre-teen children

At seven, children left the nursery and were turned over to tutors, sent to a town school, or began to learn a trade or farmwork. Some were sent to boarding schools where they wore long black robes over their clothes to signify that they were scholars. They rose with the first light of day, said prayers, washed up, dressed, ate a light breakfast and went to class by 6 am. Around 11 am they broke for dinner which was a large meal in the great hall or they went home to eat if they lived in town. The afternoon was spent on studies or work and play. Supper was around five in the evening and was a much simpler meal. Children were generally exempt from fasting and other diet restrictions imposed by the Church at this time. But some devout children chose to fast along with the adults and they were admired for their piety.

|

|

Children went to bed early, often before sunset, after saying their prayers. In boarding school, they slept two in a bed until the age of fourteen when they were adults and slept alone. Poor children slept at home in the same bed with their siblings or parents. Not only was it to keep warm but because beds were very expensive. Even the wealthy usually only had real beds for the adults. Children's beds were more like a hay pillow in a frame called a crib or they slept on hay mattresses on the floor. After the age of seven, children only slept with siblings of the same sex, a dog or two on cold nights, and not just a few bugs. Even the aristocrat's children shared their bedrooms with their siblings and their servants. Sleeping alone was considered odd, lonely, and sad.

Privacy was not cultivated as it is now. Children, especially those under the age of seven, would play outdoors completely nude without raising an eyebrow. Older boys would go swimming or play in the rain naked, girls would wear only a lightweight underdress. Boys would strip to do strenuous labor or athletic events. Boys also thought nothing of relieving themselves in the streets or defecating off a bridge. Girls were much more discrete, using a chamber pot or a privy. They used a handful of hay or dry leaves for wiping. The wealthy could afford to cut up old blankets or rags for bumwisps, but there is no record of washing hands afterward, even though handwashing was encouraged upon waking, before eating, and before bed.

Playtime

After school and chores, children were sent outside to play, unsupervised or in the company of older children. Their main activities were running, jumping, skipping, singing, dancing, hunting, fishing, catching birds, casting stones, climbing trees, wall-walking and other balancing games. Children also played group games like hide-and-seek, blind man's bluff, leapfrog, horses, piggy-back riding, vaulting, acrobatics, and wrestling. They played with toys like hoops, windmills, balls, throwing sticks, hobby-horses, skip-ropes, jacks, marbles, tops, stilts, tree swings, seesaws, shuttlecock (badminton), quoits (croquet), skittles (a bowling game), closh (kind of like golf), football, and tennis. Children and adults alike played cards, dice, and board games that included chess, draughts (checkers), tables (backgammon), fox and geese, nine-men-morris, and many chase based board games like Snakes and Ladders and cribbage. These could be drawn on the ground and played with counters made of pebbles, cherry pits, or whatever was handy. Knucklebones of sheep were used like dice to play a wide variety of games.

|

|

For the older children there were dexterity games played with bones, coins, and knives. In mumbly-peg a wooden peg was hammered into the ground with the butt of a knife then the two contestants perform a series of knife tricks. The first one to fail had to pull the peg out of the ground with his teeth. Wealthy children also spent time hunting, hawking, and riding horses for sport. Foot races and other forms of athletic competition were encouraged. Foot races for girls and boys were held at local fairs and religious events and prizes were given.

In fall and winter children made conkers by attaching threads to chestnuts to make pendulums. Then they would challenge each other to see whose conker was strongest. While trying to smash their opponents concker, they often missed and "concked" someone on the head or knuckles. Snow and cold weather provided a whole new set of playtime activities. They built snow forts and had snowball battles. They went skating on the ponds and creeks with skates made of bone and sledding on hills and on the ice. However, there is no evidence that children went skiing until the mid 19th century. Spring brought a change of weather and a chance to play with baby animals. Summer was a time to catch birds and insects, swim and play in the water, make flower chains, and wander the countryside.

Children made up games and stories and acted out daily events. One of the girl's favorites was a mock funeral where a doll was dressed in a shroud and carried down the street while the "mourners" placed blankets over their heads and wept and wailed. Boys on the other hand, like to play at war. They couldn't pick up a stick without it becoming a sword, spear or war hammer. Children were given real weapons at an age we would consider way too young. Edward I was given two arrows (and presumably a bow) at the tender age of only five. Henry V got his first sword at age nine and his son Henry VI was provided with several swords and a suit of armor at age eight. Margaret of Alnwick, sister of Henry VII shot her first buck with a bow and arrow at age fourteen.

Learning and Work

|

|

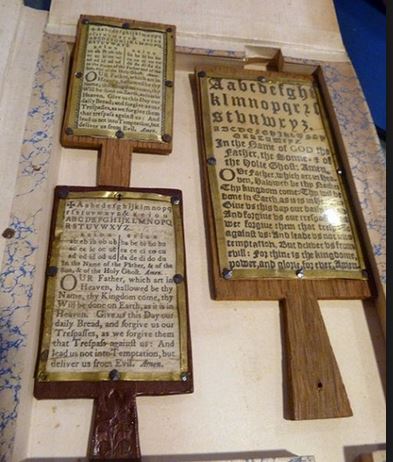

Since education was not compulsory by law in England until the 19th century we tend to think that people in the Middle Ages were illiterate but quite the contrary is true. Most children learned to read, either at home, in church schools, or town schools. Until the 14th century most schools charged a fee for attendance, then a German movement to provide free education led many municipalities to offer free schooling, at least to the boys, and in some towns, girls as well. This was seen as an investment in the wealth and piety of the community as a whole. Girls also learned to read at home or were sent to nunneries for schooling and "finishing" which meant learning gracious behavior. Teaching at home increased at this time and the textbook was the Bible, newly translated into the local language and printed on movable-type presses that made books affordable. Even children could buy coverless children's books of just a few pages stitched together for a penny. In some cases it was the children who were teaching what they learned in school to their parents at home. Hornbooks were also used to teach the alphabet from the mid-15th century until the 1900s. Hornbooks were wooden paddles covered with transparent sheets of horn. There was a sheet of parchment fastened between the two layers. Letters and words were printed on the parchment. Children could actually trace the letters on the transparent horn and then wipe them off. No doubt more than one hornbook was used to clobber a fellow student when children got angry.

Growing Up

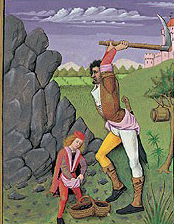

Learning a profession like farming, carpentry, or candle-making was just as important to a medieval child as learning to read or do math. Therefore as soon as they were able, they began to learn to do what their parents did or they went into an apprenticeship to learn a different profession. While some young women studied to become brewers, artists, merchants, dyers, weavers, tailors, or midwives, most girls prepared for a life of running their husband's households. This was not an unimportant job and it took many years to master. Girls learned to clean house, cook, bake, manage servants, weave, sew, garden, raise small animals, and tend the younger children. They learned the arts of shopping; how to haggle, how to spot bad quality and avoid it, what things were worth, how to budget and plan ahead. This took an understanding of math. They also learned to forage for medicinal herbs in the woods, compound medicines, treat all kinds of wounds, and even how to set bones since physicians were rare and very expensive. Boys worked with their male relatives in the fields, mines, stables, and workshops. At first they could only do small jobs like run messages or clean up. But by the time they were 13 they could do nearly any job in their father's workshop.

At age seven, a child was deemed old enough to be able to protect himself and therefore could enter into a contract, even to dedicate the rest of his life to the clergy, enter a convent, or be engaged to marry. A child of seven could be charged with a crime and even put in prison if found guilty, but this was rare if his parents were alive. In the 10th century a child of 12 could be tried for capital cirmes and killed if found guilty. By the 14th century children were not allowed to swear oaths or sign contracts until they were 14 and couldn't be executed. If they stole or damaged property, their parents were taken to court instead. In England, sending your own children away to work and taking a young ward or servant was so common it was hardly even mentioned in literature. Some children left home for work as early as age seven, but the average was for boys to leave around 12 or 13. Otherwise boys stayed at home until they took over their father's business or made enough money to buy their own. Girls stayed until they were married or became spinsters and never left.

|

|

The typical age for apprenticeship was 14, though some professions in art and music required starting much younger. This was a contractual arrangement that lasted up to 9 years. The apprentice promised to work at a reduced wage and his parents were required to put in a contribution as well. In return, the master promised to teach the apprentice a trade and hold no secrets back. He promised to feed and clothe and chastise (punish) the youth appropriately as a father would. At the end of the apprenticeship, around 20 to 22 years old, the youth would become a journeyman, free to travel and find work in other workshops and thus gain more experience. When he felt he was ready to settle down and open his own workshop, he would petition the guild to become a master. This would be granted by the guild after they examined his work and character and judged it worthy. Those that lived on tenant farms before the 15th century were called serfs and were not allowed to move away and take up a trade. But it was nearly impossible to enforce, so many children ran away to the cities where there was more opportunity.

At 14, girls reached the age of majority and were legally adults, considered old enough to inherit, marry, and bear children. Boys on the other hand didn't reach the full age of majority until 21 in England. If they inherited property before that age, it was administered by adult relatives. If the adults didn't want the responsibility they could sell that right to wealthy aristocrats who could cheat the children out of their inheritance before they reached majority. Eventually laws were enacted to protect young men from such practices and the age when boys could take over their late father's business was lowered to 14 if the child was capable of running the business.

References:

Orme, Nicholas, Medieval Children, Yale University Press, © 2001

|

If you want to add this article to your list of favorites or email it to a friend, please use this permanent URL, https://stores.renstore.com/-strse-template/1308A/Page.bok. Permission is granted by the author to quote from this page or use it in handouts as long as you include a link back to Renstore.com. |

|

| Next Article |

|