|

| Wearing cotton or linen underclothinghelped wick sweat away from the skinand bathing was refreshing on a hot day. |

by Gael Stirler

Summers can get very hot whereever you live, even if it was in Europe in the Middle Ages. Just as you need a strategy for staying warm in winter, you also need one for staying cool in the heat. We may wonder how people wearing so many layers of clothing made of wool and heavy brocade or velvet stayed cool without air conditioning. It was hot in the summer then just as it is now, so how did they cope?

Fashion

To start, they wore natural fiber fabrics which are much more comfortable than man-made viscous cloth like nylon and acetate. Ancient Greeks wore cotton togas, but in the early Middle Ages, men and women wore clothing made from other natural fibers like wool, linen, and silk all year long. By the 8th century, cotton was grown in Egypt, Spain, and India and was imported into Europe through Italy and Holland. Cotton fibers are shorter than wool making it difficult to spin with a drop spindle. It was very expensive to make cotton fabric until the late 14th century when the spinning wheel was introduced to Europe.

|

| Cotton didn't become popular in Europe untilafter the introduction of the spinning wheel. |

Cotton is known as a cool fabric now but linen worn next to the skin has unique cooling properties. It wicks moisture away from the skin and to the surface where it can evaporate. This is why people wore linen shifts and chemises under their wool clothes even in summer. Wool alone is hotter than it is when worn with a layer of linen underneath.

|

| Décolletage (a low neckline) helped todispell heat from the body. |

The décolletage women wore was not just a fashion statement; it was also to allow heat to escape. When it got hot, all she had to do was daub the naked skin between her neck and bosom with rosewater on a handkerchief for instant refreshment.

Little children were allowed to run around naked or dressed only in a shirt or chemise until around 7 years old. Then they had to dress like little adults.

Another trick was to keep the head covered with a white cloth. Men wore small white caps or biggens that could be soaked in cool water. The water evaporated when the caps were worn wet, and cooled the blood, which cooled the body through circulation. Workers also wore straw hats that could be soaked in water the same way creating both shade and evaporative cooling.

|

| Damp veils were worn to keep the head cool. |

Veils and turbans served the same purpose. They could be dampened and worn on the head or over the shoulders. You’ll be surprised at how effective they are at keeping you cool. Whenever you see a veil that is limp and transparent it is probably a damp veil meant to keep the wearer cool.

Unless a woman was an eligible bachelorette she wore her hair up off her neck. This was not only cooler but also kept her hair clean and neat. Veils were worn to protect the neck from draughts in the winter and sun in the summer. The veil could be arranged in marvelous ways to take advantage of a breeze or block the glare of sunlight on her eyes. They could also be wrapped around the face to protect from dust and bad smells.

To avoid sunburn, women wore small shawls or kerchiefs over their shoulders and long veils. Heavy long sleeves were uncomfortable but short sleeves invited burns. This led to fashions with convertible sleeves that tied or buttoned on or had slits in them. Big puffy sleeves created a cushion of air around the arm that provided insulation from the heat of the sun so they were popular in Italy when tight sleeves were fashionable in Northern climes.

|

| Large, puffy sleeves, popular in Italy, served toinsulate the arms from the hot sun. Partlets ofsheer white fabric protected the shoulders andback from sunburn. |

Heavy wool or brocade skirts were stifling around the legs so women wore bum rolls, hoop skirts, and crinolines under their dresses to hold the skirts away from their legs. This made the skirt more like a shade tent over their legs creating a nice cool microenvironment.

Accessories

|

| Woman cooling off by turning up the lined skirt ofher coathardie toreveal her kirtle. |

When women wore more than one skirt at a time and the top skirt was lined, they would flip the top skirt up, revealing the lining, and pin it at the waist. If it parted in the front, they would bustle it over the hips and pin it in the back. Long trailing skirts were also bustled up in the back and if it was really warm, the whole skirt was belted at the waist and pulled up until the hem was above the ground. The excess fabric flopped over the belt creating a kind of peplum.

Women are shown using fans made of feathers, parchment, or even leather. Some are in the shape of flags and painted with heraldic emblems. Some fans were designed to shield the user’s face from heat when sitting by the fire. Large fans on long sticks were not only used to create breeze but to shade people and keep the sun out of their eyes.

|

| Fans were used to create abreeze and to shield the facefrom heat and glare. |

Umbrellas and parasols were rare in the Middle Ages in Europe being used only in religious processions by popes and doges. In the 16th century knights rode out with parasols to prevent their armor from getting too hot, and parasols were used by famous women like Catherine de Medici, Mary Queen of Scots,and Elizabeth I. In 1592 Michel de Montaigne commented that they seem to be more of "a burden to the arm than a protection to the head" when the ladies of Lucca, Tuscany carry them.

In the Home and Marketplaces

Homes in Mediterranean countries were built to take advantage of the prevailing breezes. They were built around central courtyards with fountains and gardens that created a cool shady environment for the inhabitants. Bowls of water were set out around the home to evaporate and cool the air. Servants hung Wet cloths on windows and doorways to catch a breeze and provide some cooling.

|

| Cupid standing under the pergola has justshot the lover in the heart with a bolt. |

They planted their gardens with cypress and other tall trees that provided shade. In the center of the garden, a fountain provided the welcome sounds of water and a cooling effect on the surrounding air. They built pergolas and arbors in the garden with vines trained on lattices for covered walkways and sitting areas. When the rest of the house was stifling hot, people would retire to these shady spaces to stroll, rest, eat, and converse.

Instead of holding markets in the open air as in the rest of Europe, the markets in Italy, Greece, and Turkey were held in large buildings or covered streets where merchants and shoppers were less exposed to the relentless sun.

In summer, the coolest buildings were usually the churches and mosques with their thick walls and high ceilings. They provided a haven from the heat and were popular meeting places for business as well as religious activities.

|

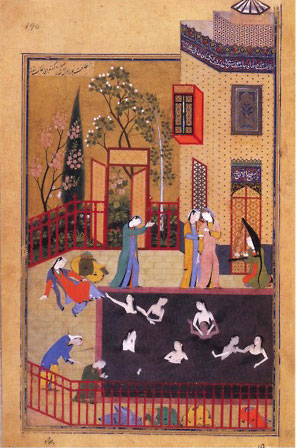

| Ladies swimming in a Persian illuminatedmanuscript from the Safavid dynasty. |

Bathing and swimming were pleasant pastimes when it was hot whether it was in a pool, fountain, river, lake, or grotto. However, swimming in the ocean for fun was virtually unheard of. The only pictures of swimmers in the ocean are of people who were shipwrecked or performing some kind of work, like sponge diving.

When it was too hot to work in the afternoons, it was the custom in Spain and Italy to take a siesta or nap, then work late into the evening.

Food and Drink

Food was prepared fresh from the garden or butcher, as quickly as possible, so it wouldn’t spoil. This meant shopping for food everyday. Some foods were preserved to make them last longer, like salami and dried fish. If they had access to ice, it was harvested in the winter and kept in straw in the basements of their castles. These castles had iceboxes of stone in their kitchens for storing some food and drinks. For parties the wealthy would keep bottles of wine cool in large basins filled with ice. These were often elaborately covered with painted figures. However, most people kept their drinks cool by putting them in jugs wrapped in wet cloth or grass fiber.

All across North Africa a refreshing Maghreb tea made with green tea, fresh mint, and sugar or honey was served at any time of day. Traditionally made by the male head of the house and served to guests with great ceremony, it was considered impolite to refuse it.

Lemonade and Lemonana, a lemonade made with mint, were refreshing summer drinks enjoyed in Italy and Palastine. Sekanjabin, made with sugar and vinegar, and Oxymel which is made with honey and vinegar were popular in Persia and Greece. The sweet and sour flavor makes the mouth water and the mint cools the throat making this a very pleasent summer beverage when served cold.

The following section of recipes is from an article by Jehanne de Huguenin

Oxymel

From an Anglo-Saxon Leechbook, Cockayne p. 285

Take of vinegar, one part; of honey, well cleansed, two parts; of water, the fourth part; then seethe down to the third or fourth part of the liquid, and skim the foam and the refuse off continually, until the mixture be fully sodden.

Cariadoc’s Sekanjabin recipe

Dissolve 4 cups sugar in 2 1/2 cups of water; when it comes to a boil add 1 cup wine vinegar. Simmer 1/2 hour. Add a handful of mint, remove from fire, let cool. Dilute the resulting syrup to taste with ice water (5 to 10 parts water to 1 part syrup). The syrup stores without refrigeration.

Note: This is the only recipe in the Miscellany that is based on a modern source: A Book of Middle Eastern Food, by Claudia Roden. Sekanjabin is a period drink; it is mentioned in the Fihrist of al-Nadim, which was written in the tenth century. The only period recipe I have found for it (in the Andalusian cookbook) is called "Sekanjabin Simple" and omits the mint. It is one of a large variety of similar drinks described in that cookbook - flavored syrups intended to be diluted in either hot or cold water before drinking.

Syrup of Sekanjabin Simple

An Anonymous Andalusian Cookbook of the Thirteenth Century, tr. Charles Perry.

Take a ratl of strong vinegar and mix it with two ratls of sugar, and cook all this until it takes the form of a syrup. Drink an ûqiya of this with three of hot water when fasting: it is beneficial for fevers of jaundice, and calms jaundice and cuts the thirst, since sikanjabîn syrup is beneficial in phlegmatic fevers: make it with six ûqiyas of sour vinegar for a ratl of honey and it is admirable.

(The same collection gives a recipe for a syrup of mint, made with mint and other herbs, sugar and water).

References

Cariadoc’s Miscellany, © David Friedman and Elizabeth Cook, 1988, 1990, 1992

http://www.pbm.com/~lindahl/food.html

Rev. Thomas Oswald Cockayne Leechdoms, Wortcunning and Starcraft of Early England, (1961) London: Holland Press

Hippocrates, On Regimen in Acute Diseases, tr. Francis Adams

http://classics.mit.edu/Hippocrates/acutedis.mb.txt

Platina, On Right Pleasure and Good Health, tr. Mary Ella Milham (1998) Tempe: Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies

|

If you want to add this article to your list of favorites or email it to a friend, please use this permanent URL, https://stores.renstore.com/-strse-template/1406A/Page.bok. Permission is granted by the author to quote from this page or use it in handouts as long as you include a link back to Renstore.com. |

|

Previous Article Previous Article |

Next Article  |