by Gael Stirler

(April, 2013)

|

|

As much as cars and the internal combustion engine defines our age, the horse defined the middle ages in Europe. Horses, along with mules and donkeys were relied on for transportation, agriculture, war, and recreation. A large segment of the population was dedicated to occupations that used or cared for horses. The language used to describe the animals and their handlers can be confusing to the modern reader. Many of the terms are used differently now, so if you want to read historical fiction or do research on the middle ages it is important to understand what they were talking about.

Horses were not referred to by their breed but by their purpose. Therefore, many of the modern breed names had broader, less specific meanings in the middle ages. Horses were measured in hands, not in inches--with each hand being 4 inches high (three hands to the foot). The average horse in the middle ages was 13 to 14 hands high at the withers (shoulders) and would look like a pony or small horse to us today. But then, the men and women of the middle ages would look small to us as well.

|

|

Types of Horses

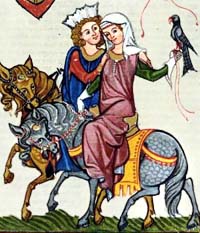

Elegant-looking, warm-blooded, (mild-mannered) horses with a smooth gait were bred with other similarly tempered horses to create "amblers" also known as "Palfrey horses." These were highly prized by the upper classes because they were very comfortable to ride on long journeys. These light-weight, riding horses were also used in battle because they could move quickly and were sure-footed on uneven ground. The prettiest palfreys were reserved for parades and special care was given to their grooming.

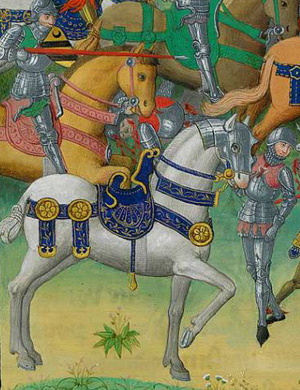

Destriers or great horses were larger, hot-blooded horses bred to be fearless in warfare. Though they were larger than Palfreys, contrary to some common belief, they were not as large as modern Clydesdales. Based on existing horse armor, the size of destriers is estimated at no more than 15.2 hands high with a weight of 1200 to 1300 pounds, about the size of a modern show horse. A horse this size could easily carry the weight of a knight in full armor including saddle, barding, tack, and weapons. Larger horses were used to pull cannons and wagons and rarely saw combat. Destriers were also used in tournaments where speed and agility were important. Destriers were hot-blooded, meaning they were spirited, fearless in battle, and would even attack other horses by biting and kicking.

|

|

Another type of hot-blooded horse was called the Charger or Courser. These terms were used interchangeably for fast runners. They were used as messenger horses and racers. The wealthy brought an average of five horses with them to war, a couple palfreys for travel and parades, a Destrier for battle, and a pair of swift chargers for escape.

Dray or Draft horses, on the other hand, were cold-blooded and docile. They were bred for commercial uses like hauling, plowing, and turning mills. These big horses came from Northern England (Shire horses, Fell 'ponies'), Scandanavia, and the Netherlands (Fresians) and were known for plodding gaits and massive strength. Some were 18 hands high and weighed as much as 2000 lbs.

A Jennet was a small horse or pony, bred for walking, and the favorite of ladies. Jennets were good for pilgrims since a small horse ate less and was easier to care for than the larger Palfrey. They were also used as light cavalry horses.

|

|

The Rouncey was an all-around good service horse. This is the kind of horse the squires and other travelers rode. A hackney was a rouncey for hire. Not everyone owned a horse. Some people rented them when they traveled. Rounceys and hackneys were valued at no more than 20 marks in France in 1265 AD, where the finest destriers might fetch more than 500 times that price!

Pack and cart horses along with mules and donkeys, had to be docile and easy to handle. Older rounceys or nags had the right temperament making them good for commercial use in hauling goods. They were the proverbial workhorses.

Ponies were horses that were bred to be small, strong and hardy to pack coal and ore out of mines. They were also ridden and used with wagons or carts. When looking at paintings, you can tell it's a pony if a rider's feet hang noticeably below the mount's belly. However, the terms horse and pony were used interchangeably in the middle ages and not in the way they are defined by horse breeders today.

Equine technology

The Roman horses didn't wear horseshoes as we know them, they wore a hipposandal that looked like a metal boot for the horse hoof. For the most part, nailed horse shoes were unknown prior to the tenth century. The earliest evidence comes from a written record of "crescent figured iron with nails" as part of the a list of cavalry equipment in 910 AD. By the 11th century horseshoes were commonly used in Europe to protect the horses feet.

|

|

Stirrups were developed in China in the 5th century and were widely adopted in Europe by the 8th century. Stirrups gave riders a more secure perch on the horses back. Riders could shoot arrow, javelins, and swing swords with more accuracy and power when standing in the stirrups. This was a huge advantage that turned the tide in many battles and gave rise to feudalism.

At first saddles were just leather pillows belted onto the horse. Solid-treed saddles were first used in Roman times as a means of spreading the weight of the rider over a wider area of the horses back and away from its spine, thus making riding safer and more comfortable for both the rider and horse. Due to the heavier weight of armored knights, the medieval saddle had to be bigger with a higher front and back than earlier saddles to keep the knight from being unhorsed. The use of the solid-treed saddle also made stirrups more effective.

Since a knight's hands were often occupied with weapons, he had to control his mount with his legs and feet. Spurs were used to communicate the rider's commands by kicking or nudging the horse's sides. Wearing spurs was a privilege reserved for knights and a symbol of rank.

The armor for a horse was called barding. The horse helmet was called a chamfron and was designed to protect the face. The segmented plates covering the neck were called the criniere. The breastplate or peytal covered the shoulders and chest and the croupiere covered the hindquarters. For tournaments, the armor was covered with colorful embroidered cloths that identified the knight by his heraldic emblems. These coverings were known as caparisons.

|

|

The padded horse collar created a revolution in agriculture. This made it possible for one horse pulling a wheeled turn-plow to work as much land in a day as a pair of oxen. Two horses could finish the work in half the time. This lead to higher yields per acre and greater prosperity in Europe during the 12th century. At this time European farmers adopted three-field crop rotation to increase the fertility of their land. Horses made it possible to plant and harvest two crops a year and still have time to let the soil rest for one season.

Horse professions

The most elite job, of course, was knight, a position for the upper classes that required training from childhood in all matters of horse management and the arts of war. The word for knight in most European languages means "horseman." A squire was a young man in training to become a knight. Squires were not allowed to buy or ride horses that were expensive, even if they could afford it, lest they looked better than their knights.

In most great houses, the marshal was the person in charge of all matters relating to horses. He managed the stables, hired all the grooms, trainers, stable boys and stall muckers, arranged for the fodder, assisted in buying and breeding horses, and oversaw the hunt and travel. In most cases the marshal also provided basic general veterinary care to the animals.

The constable (count of the stable) was the lieutenant to the marshal and kept order in the stables and yard. The marshal and the constable arranged all the tournaments and parades and were also responsible for all military preparation of the horses and their equipment.

The farrier was a specialist in animal hoof care. Sometimes they made horseshoes but more often they left that to the blacksmith who owned a forge. The farrier traveled to the stables and shooed the horses, cleaned the hooves and treated injuries.

Horse coursers, dealers, and traders sold and traded animals. Some captured wild horses and trained them.

Hackneymen rented horses, wagons and carriages. They also provided carriage service for hire in cities.

Grooms exercised the horses and keep them clean. Stable boys didn't work with the horses until they were grooms. They cleaned the stalls, fed the animals, and hauled water and fodder.

Tinkers, were a nomadic people in the British Isles, also called travellers and gypsies. They spoke dialects that were strange to the settled people and they observed many old superstitions, but they were best known for trading ponies. They still hold annual horse fairs around England as they have for many centuries. Because of their strange and secretive ways, they were often accused of using witchcraft to enchant horses and to heal them. Only in the 20th century was it obvious that the gypsies had been using techniques we now call horse whispering and a primitive form of penicillin to cure horses by binding moldy bread and leather straps to their wounds.

|

If you want to add this article to your list of favorites or email it to a friend, please use this permanent URL, https://stores.renstore.com/-strse-template/1304A/Page.bok. Permission is granted by the author to quote from this page or use it in handouts as long as you include a link back to Renstore.com. |

|

| Next Article |

|